|

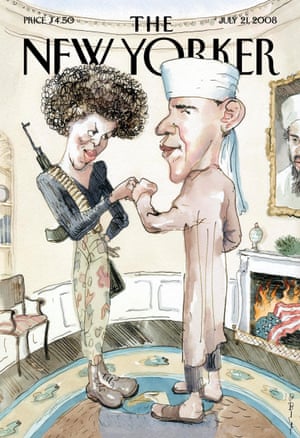

| The New Yorker’s offensive cover of July 2008. Photograph: Reuters |

When was the last time we readily believed in the words of a politician? Simple – listening to Barack Obama give a tribute to the sheer brilliance of his wife, Michelle, at his farewell speech. Call it schmaltzy or sentimental, their love, even from this distance, seems real. At work, colleagues huddled around tiny phone screens to watch Obama tell the world that he was proud of his wife and the grace and dignity with which she made the office of first lady her own. We cooed and aahed as though over a baby.

Inauguration day draws ever nearer, and as it does my wish to escape the inevitable intensifies. This feeling is unquestionably about a president who has brazenly lied his way to the top. It is about the unsuitability of a petty man full of bluster and bile accustomed to getting everything he wants because he has always had the means to do so. But the injustice of it feels more naked and insulting, as in exchange for Trump we lose the Obamas – all of them: plural not singular.

I say we, because the Obamas have never been a family that belonged solely to Americans. Obama’s African ancestry and the family’s cool aesthetic make them relatable to those beyond American shores. Africans, in particular, some of the best placed people to view Obama’s legacy as stained by his deployment of drones and a lack of investment in the region, still share in the brilliance of Obama story.

Before their eight years in the White House, the idea in the popular imagination of black family life involved embattlement or dysfunction, or both. To remember how debased the narrative was, think back to nearly four months before Obama was elected president, when the New Yorker magazine’s July edition showed a now infamous cartoon under the headline “the politics of fear”. In the illustration Obama, dressed as Osama bin Laden, is engaging Michelle in a fist-pump.

|

| The Obamas on election night in Chicago in 2012. Photograph: Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images |

The soon-to-be first lady is sporting an afro (that potent symbol of radical black politics, though this is what our hair, if left to grow naturally, looks like), combat boots and an AK-47. The editor, David Remnick, had intended a sketch that would satirise those who had indulged in “rumours, innuendo [and] lies about the Obamas”. Irrespective of its intent, it was offensive precisely because it gave voice to the highly prevalent and very toxic sentiments held about them as a couple.

Blackness, for many, meant that the family could be seen as part of a fifth column intent on undermining the nation. Which is to say that being black has consistently been viewed as threatening, a sign of an everlasting separateness. It is the subtext of commands to “go back to Africa/home/wherever you came from” many of us living in majority-white nations have, no doubt, encountered. Because however “integrated” we may be, our skin forever marks us as mere interlopers destined to disrupt and contaminate the purity of the nation.

Michelle, Sasha, Malia and Barack Obama will be missed sorely. Among the myriad reasons, not least is the vision of black familial love they have graced upon us. It has been the most powerful antidote to corrosive, hate-filled politics. Over the past eight years, in the manner of putting on a beloved, comfy oversized jumper, I have Googled “the Obamas” and scrolled through images of a loving, successful black family as though I were basking in the warmth and glow of a wood burner. In that time their beauty and resilience seemed only enhanced, rather than tarnished, by the unwavering gaze that comes with the role.

|

| Malia, left, and Sasha at the White House Christmas tree lighting in 2015 Photograph: Olivier Douliery/EPA |

One can trace slavery and colonialism, migration and the wonderful ability of black people to remain hopeful, making life anew despite the devastation heaped upon them. From insurance, to health, to housing and, of course, employment, being black means being awarded crisscrossing disadvantages that will augment over the course of a life. The story of the Obamas, though, is more than this familiar one of black victimhood or its corollary, black super-strength.

Something about them, existing as they do in a separate stratosphere, has the suggestion of daily life that all can relate to. You can find images of them barefoot, in lounging attire, food strewn across a footrest while watching the World Cup, or snow-fighting on the White House lawn. Numerous others show them sharing laughter or playfully teasing each other. Their closeness seems true and profound, and is a picture of wholesome family life that has, for once, been given a black face.

|

| Michelle and Barack and their daughters Malia and Sasha board Air Force One. Photograph: Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images |

Better yet, they have done all of the above not by resorting to a dignified distance characterised by the stolid gentility of many heads of state. With their meaningful fist-pumps and love of hip-hop, they have eschewed “respectability politics” and chosen to embrace, rather than disavow, their black cultural identity.

The Obamas are not like you and I. Their experience is far removed and, when you think about it, fantastical. All that said, they have humanised the presidential office and principally done so by holding on to the primacy of family.

Both parents have continuously publicly shown affection to each other and their children. This is radical in itself because there are not enough representations of such black familial love to understand it is this very thing that sustains us and allows us to navigate a world structured against our every endeavour.

|

| The Obamas with Michelle’s Portuguese water dog Bo in 2009 Photograph: Saul Loeb/AFP/Getty Images |

theguardian

No comments:

Post a Comment